Fear

I've had a couple email exchanges with cousin John Kane about our shared fear of public speaking. It reminded me that I'd worked through this a couple years ago and even wrote about it a bit. Here's what I had (and have) to say about that.

**************************

The Eagle is a square-rigged sailing ship that the U.S. Coast Guard Academy uses to train cadets. While at the Academy, I spent part of four summers in the North Atlantic on board Eagle learning the finer points of seamanship. The ship has three masts that rise 150 feet above its teak decks. To set and furl the top-most sail, the Royal, you climb a spider web of ropes and rope ladders to the Royal yardarm and then inch your way out to the end of the yard while standing on a rope the diameter of your thumb. While you are climbing and hanging on, the mast top swings in a dizzying arc through the sky as the ship rolls in the sea far below. There are no safety belts or lines – only the bosun’s admonition of ‘one hand for the ship, one hand for yourself.’

The first time I went aloft I was nearly paralyzed by fear – I had to force myself to reluctantly relax my grip and move one hand a few inches upward to clutch the next rung. Then pause, take a few breaths – making sure not to look down – and will the other hand to move. Until then I hadn’t known that I had any fear of heights. But I persisted. I was 18 years old and surrounded by 150 other young males. Some combination of peer pressure and youthful machismo propelled me upward. Amazingly, within a week or two I was scrambling to the top of the masts without hesitation and even sliding down the backstays from the upper crows nest for a lightning return to the main deck.

Decades later I was in a relationship with a partner who thrived on argument and confrontation. It was a mismatch – I had grown up in a family where arguing was not a sport. I had little ability to assert myself and when confronted would freeze up, literally unable to speak. Immobilized by fear. Surprisingly, this reaction did little to help resolve conflicts or improve communication. But I persisted. Some combination of partner pressure, aging machismo and intellectual curiosity propelled me in the direction of a cognitive behavioral therapist – I wanted to figure out why I reacted with such fear and perhaps even change that reaction. Along the way I learned some things about fear and its many uses.

Fear is a vital emotion. Our species – most species, in fact – would not survive without fear. My reaction of freezing while first climbing the mast of Eagle or when confronted by a partner’s anger is part of the same response that causes a deer to freeze in your car’s headlights – it is a survival reaction that operates more quickly than conscious thought. Three common fear or survival reactions are freezing, fleeing, or fighting. I have typically used the first two but all can be effective – it depends on the nature of the threat. The fast fear-driven responses save us from imminent threats. Nowadays, we seldom have to escape tigers or lions, but these responses still often serve us well – they are what kicks in when we need to jump out of the path of a car running a red light.

So, we don’t want to rid ourselves completely of the fear response. Anxiety or long-term fearfulness, however, is a problem in modern societies. We often react with fear and operate in a constant state of anxiety even when there is no real, imminent danger. The trick is to tame the fear response so that it happens only when really needed and, as a by-product, reduce long term anxiety.

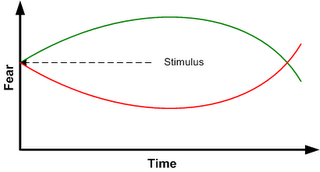

Let’s look at some graphs that describe two different ways to respond to fear. The following diagram illustrates what happens when you respond to a fearful situation by avoiding it – the instinctive reaction;

If I avoid the source of fear I immediately reduce my level of fear or anxiety. Whew! Got out of that safely! Didn’t die this time. However, over time my anxiety will likely increase – my perception of the threat has not lessened, I just temporarily removed myself from the source. It’s possible, even likely, that in the long term my anxiousness may actually increase to a level higher than is was initially because I become increasingly apprehensive about this unresolved fear.

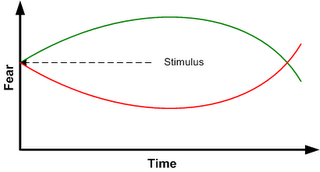

The next illustration shows what happens if instead of avoiding the source of fear I actually approach or confront it:

If I approach source of fear, the immediate result is an increase in fearfulness or anxiety. That’s what nearly paralyzed me in my first attempts to go aloft on the Eagle. However, if I persist and don’t completely freeze or flee, the fearfulness begins to subside with additional exposure. The brain discovers that perhaps you can actually survive this situation and decides that it can relax a bit. And maybe even completely let go of the fear – eventually. And the two arcs of fearfulness that result from approach versus avoidance may ultimately cross:

This suggests that repeated confrontation or exposure to a situation that scares me may reduce the response to a point well below what happens if I continue to avoid the situation or stimulus.

OK. That’s theoretically interesting. But can this information actually be of help while I try to get through each day? My personal experience is promising.

I no longer have the opportunity (nor the desire) to climb the mast of a sailing ship. But I was still challenged (ok, threatened) by conversational confrontations. I had always been shy and had an inordinate fear of speaking in public. And I had finally figured out that I also was unable to speak (or think clearly) in private – if the conversation might become confrontational or emotional. So, based on my slight understanding of the approach/avoidance concept, I decided to very intentionally confront my fear of public speaking. I joined a group (Toastmasters) that seemed like it could help me overcome this unreasonable fear. It worked. I was nearly paralyzed during my first speech at Toastmasters but quickly became comfortable giving little speeches and talks. I learned that I could push through fearfulness if I just confronted it. I had done that when climbing Eagle’s masts but it had been completely unconscious. This time I had actually figured out the source of the fear and determined how to get past it.

But so far, I’d only learned how to deal with a specific fear reaction – with the most recent success being how to not panic or freeze when I had to speak in public. Was there a way to extend that knowledge and success so that I might reduce fear and anxiety in other situations?

I stumbled into this next piece of the puzzle while participating in an ongoing series of mindfulness meditation teachings. At the end of one of these practices, the teacher gave us an assignment to help us become more mindful and aware even when we weren’t formally meditating. She suggested picking some mundane event that happened naturally during our day and using that event as a trigger to ‘pay attention’ – to bring ourselves into the present moment. Any trivial common event could be used - for example, the sound your computer makes when you get an incoming email or the reminder of an upcoming meeting.

I decided to use as a trigger a very minor anxiousness that I frequently experienced at work. The office where I work has three long parallel hallways that run the length of the building. When I was walking down a hallway and saw someone that I didn’t know approaching, I would usually duck over to one of the other hallways to avoid contact with the stranger. It was a silly response and habit, born of life-long shyness. But it was a minor and real source of slight anxiety – and it happened often every day. Perfect! Each time I saw someone approaching and felt that slight anxiousness and impulse to take a different path, I reminded myself to become aware and pay attention to what was happening. I turned this trivial source of fear into an opportunity for mindfulness. (A happy by-product of the practice was that soon most of the ‘strangers’ became comfortable co-workers.)

The important lesson I learned was that I could actually use the fear response as an opportunity for change. Just two things were required to make this work: becoming fully aware of the sensation of fear and then be willing to stay with that sensation and not immediately avoid it. (Unless, of course, the fear is in response to an immediate and real threat that requires action.) Since fear or anxiety usually produce a very real physical sensation – that funny sensation in your gut or tensing of muscles for example – with practice you can detect the early signs of anxiety and become fully aware of it. And then turn it into a calming meditative experience.

My personal experience and the examples I’ve described all deal with very minor levels of anxiety – I’ve had few big traumas in my life that I needed to deal with. But a reading of current medical and scientific literature indicates that the techniques I stumbled into are the same ones being used by medical professionals for the treatment of such things as post-traumatic-stress-disorder and other anxiety reactions. Research indicates that practices such as mindfulness meditations and repeated exposure to situations that trigger an anxiety – especially when these two techniques are combined - can be as effective as pharmacological treatments for anxiety. And unlike extended use of such medications as Prozac, these alternate approaches offer the possibility of eliminating the anxious response instead of masking them.

I’m not a medical professional. I won’t claim that the approaches I’ve practiced and described would work for everyone or in every situation. I do believe and suggest however that, to paraphrase Franklin D. Roosevelt, ‘we have nothing to fear, not even fear itself.’

**************************

The Eagle is a square-rigged sailing ship that the U.S. Coast Guard Academy uses to train cadets. While at the Academy, I spent part of four summers in the North Atlantic on board Eagle learning the finer points of seamanship. The ship has three masts that rise 150 feet above its teak decks. To set and furl the top-most sail, the Royal, you climb a spider web of ropes and rope ladders to the Royal yardarm and then inch your way out to the end of the yard while standing on a rope the diameter of your thumb. While you are climbing and hanging on, the mast top swings in a dizzying arc through the sky as the ship rolls in the sea far below. There are no safety belts or lines – only the bosun’s admonition of ‘one hand for the ship, one hand for yourself.’

The first time I went aloft I was nearly paralyzed by fear – I had to force myself to reluctantly relax my grip and move one hand a few inches upward to clutch the next rung. Then pause, take a few breaths – making sure not to look down – and will the other hand to move. Until then I hadn’t known that I had any fear of heights. But I persisted. I was 18 years old and surrounded by 150 other young males. Some combination of peer pressure and youthful machismo propelled me upward. Amazingly, within a week or two I was scrambling to the top of the masts without hesitation and even sliding down the backstays from the upper crows nest for a lightning return to the main deck.

Decades later I was in a relationship with a partner who thrived on argument and confrontation. It was a mismatch – I had grown up in a family where arguing was not a sport. I had little ability to assert myself and when confronted would freeze up, literally unable to speak. Immobilized by fear. Surprisingly, this reaction did little to help resolve conflicts or improve communication. But I persisted. Some combination of partner pressure, aging machismo and intellectual curiosity propelled me in the direction of a cognitive behavioral therapist – I wanted to figure out why I reacted with such fear and perhaps even change that reaction. Along the way I learned some things about fear and its many uses.

Fear is a vital emotion. Our species – most species, in fact – would not survive without fear. My reaction of freezing while first climbing the mast of Eagle or when confronted by a partner’s anger is part of the same response that causes a deer to freeze in your car’s headlights – it is a survival reaction that operates more quickly than conscious thought. Three common fear or survival reactions are freezing, fleeing, or fighting. I have typically used the first two but all can be effective – it depends on the nature of the threat. The fast fear-driven responses save us from imminent threats. Nowadays, we seldom have to escape tigers or lions, but these responses still often serve us well – they are what kicks in when we need to jump out of the path of a car running a red light.

So, we don’t want to rid ourselves completely of the fear response. Anxiety or long-term fearfulness, however, is a problem in modern societies. We often react with fear and operate in a constant state of anxiety even when there is no real, imminent danger. The trick is to tame the fear response so that it happens only when really needed and, as a by-product, reduce long term anxiety.

Let’s look at some graphs that describe two different ways to respond to fear. The following diagram illustrates what happens when you respond to a fearful situation by avoiding it – the instinctive reaction;

If I avoid the source of fear I immediately reduce my level of fear or anxiety. Whew! Got out of that safely! Didn’t die this time. However, over time my anxiety will likely increase – my perception of the threat has not lessened, I just temporarily removed myself from the source. It’s possible, even likely, that in the long term my anxiousness may actually increase to a level higher than is was initially because I become increasingly apprehensive about this unresolved fear.

The next illustration shows what happens if instead of avoiding the source of fear I actually approach or confront it:

If I approach source of fear, the immediate result is an increase in fearfulness or anxiety. That’s what nearly paralyzed me in my first attempts to go aloft on the Eagle. However, if I persist and don’t completely freeze or flee, the fearfulness begins to subside with additional exposure. The brain discovers that perhaps you can actually survive this situation and decides that it can relax a bit. And maybe even completely let go of the fear – eventually. And the two arcs of fearfulness that result from approach versus avoidance may ultimately cross:

This suggests that repeated confrontation or exposure to a situation that scares me may reduce the response to a point well below what happens if I continue to avoid the situation or stimulus.

OK. That’s theoretically interesting. But can this information actually be of help while I try to get through each day? My personal experience is promising.

I no longer have the opportunity (nor the desire) to climb the mast of a sailing ship. But I was still challenged (ok, threatened) by conversational confrontations. I had always been shy and had an inordinate fear of speaking in public. And I had finally figured out that I also was unable to speak (or think clearly) in private – if the conversation might become confrontational or emotional. So, based on my slight understanding of the approach/avoidance concept, I decided to very intentionally confront my fear of public speaking. I joined a group (Toastmasters) that seemed like it could help me overcome this unreasonable fear. It worked. I was nearly paralyzed during my first speech at Toastmasters but quickly became comfortable giving little speeches and talks. I learned that I could push through fearfulness if I just confronted it. I had done that when climbing Eagle’s masts but it had been completely unconscious. This time I had actually figured out the source of the fear and determined how to get past it.

But so far, I’d only learned how to deal with a specific fear reaction – with the most recent success being how to not panic or freeze when I had to speak in public. Was there a way to extend that knowledge and success so that I might reduce fear and anxiety in other situations?

I stumbled into this next piece of the puzzle while participating in an ongoing series of mindfulness meditation teachings. At the end of one of these practices, the teacher gave us an assignment to help us become more mindful and aware even when we weren’t formally meditating. She suggested picking some mundane event that happened naturally during our day and using that event as a trigger to ‘pay attention’ – to bring ourselves into the present moment. Any trivial common event could be used - for example, the sound your computer makes when you get an incoming email or the reminder of an upcoming meeting.

I decided to use as a trigger a very minor anxiousness that I frequently experienced at work. The office where I work has three long parallel hallways that run the length of the building. When I was walking down a hallway and saw someone that I didn’t know approaching, I would usually duck over to one of the other hallways to avoid contact with the stranger. It was a silly response and habit, born of life-long shyness. But it was a minor and real source of slight anxiety – and it happened often every day. Perfect! Each time I saw someone approaching and felt that slight anxiousness and impulse to take a different path, I reminded myself to become aware and pay attention to what was happening. I turned this trivial source of fear into an opportunity for mindfulness. (A happy by-product of the practice was that soon most of the ‘strangers’ became comfortable co-workers.)

The important lesson I learned was that I could actually use the fear response as an opportunity for change. Just two things were required to make this work: becoming fully aware of the sensation of fear and then be willing to stay with that sensation and not immediately avoid it. (Unless, of course, the fear is in response to an immediate and real threat that requires action.) Since fear or anxiety usually produce a very real physical sensation – that funny sensation in your gut or tensing of muscles for example – with practice you can detect the early signs of anxiety and become fully aware of it. And then turn it into a calming meditative experience.

My personal experience and the examples I’ve described all deal with very minor levels of anxiety – I’ve had few big traumas in my life that I needed to deal with. But a reading of current medical and scientific literature indicates that the techniques I stumbled into are the same ones being used by medical professionals for the treatment of such things as post-traumatic-stress-disorder and other anxiety reactions. Research indicates that practices such as mindfulness meditations and repeated exposure to situations that trigger an anxiety – especially when these two techniques are combined - can be as effective as pharmacological treatments for anxiety. And unlike extended use of such medications as Prozac, these alternate approaches offer the possibility of eliminating the anxious response instead of masking them.

I’m not a medical professional. I won’t claim that the approaches I’ve practiced and described would work for everyone or in every situation. I do believe and suggest however that, to paraphrase Franklin D. Roosevelt, ‘we have nothing to fear, not even fear itself.’

1 Comments:

When someone writes an paragraph he/she retains the image of a

user in his/her mind that how a user can know it.

Therefore that's why this article is perfect.

Thanks!

Also visit my web-site; femdom cam ()

Post a Comment

<< Home